About the author

Joakim Achren

General Partner @ F4 Fund, Co-Founder @ Next Games (acquired by Netflix), the most helpful investor on your cap table 🫡

Journal 5 Joakim Achren March 4

I cannot show you the exact path, but I can point you in the right direction.

The longer I’ve been a startup investor, the more evident it becomes where game company pitches fail: it’s when you pitch a game, not a company.

A typical deck introduces the company as slide number one, preceded by a team slide. Then, the deck deep dives into the game pitch and never emerges. Why is that not a good thing? First, if the game fails, the company will have an identity crisis; its whole existence was built on the idea of the game working.

As a second point, a game’s success is often only possible to know after it’s launched. Many variables, often unknown ones, will cause a perfect game to not work in the market. If the game is still in early development, more is needed to prove it could work. You could flip a coin.

But, a games company pitch could be different. In the early days of the App Store, a free-to-play game for mobile was a distribution innovation. This nascent platform was without competition, and a developer could pitch the opportunity of profitable user acquisition as a significant distribution innovation for a games company, which was still untapped.

Mike Maples Jr. is a founder partner and investor at Floodgate. In a 2020 podcast interview, he said the following.

What we’ve come to realize is that a startup isn’t really a company at all. A startup is a set of founders with a set of proprietary insights resulting from them living in the future. Most of the great startups come from a great insight, which usually occurs when someone is living in the future and they notice something missing.

— Mike Maples, Jr.

How do you apply this to gaming? In 2010, as Apple had just rolled out in-app purchases for the App Store, you could have been a founder, living in the future, seeing that the business model of mobile free-to-play would be dominant because of the paid user acquisition arbitrage, which would be the distribution innovation. All this in a market of smartphones, where the user base was destined to grow. You could have seen a big market in the future, up for grabs.

As I said earlier, I can only point you in the right direction. The best times for gaming have been when new platforms have emerged, allowing new distribution and business models. Free-to-play went from online destination sites to Facebook Canvas and eventually to smartphones in the last twenty years. Each platform allowed for an ever-stronger distribution and business model.

This emergence won’t stop on mobile. It can just take time for an even better platform to emerge. Technology needs to evolve. Apple brought out iPads and the iPhone in a span of three years, with a clear distinction between the iPhone having a small screen and the iPad having a bigger screen. These have converged into a form factor where the big screen can still fit in your back pocket.

This is not the end. As we wait for a smartphone disruptor, we look for other platforms emerging.

Spatial computing can become the computer killer, where people stop buying laptops and opt for a wearable display that makes your entire field of view into a computer screen.

Is there a founder living in the future, seeing what is missing now with Vision Pro, and then building that? The platform is nascent; a playbook for distribution and business models has yet to be written. But we know this is the future, and the platform will grow yearly. An ambitious founder will realize that the right path is in the future, not sticking to the past.

Timo Ahopelto, one of the partners at Lifeline Ventures and an early investor in Supercell, has a podcast in Finland where he and his co-host talk about everything they’ve learned about startups.

Internally, at Lifeline, they have a hypothesis for startup outcomes. This hypothesis consists of the likelihood of success times the ambition level of the founder. Lifeline believes the likelihood of success is constant, whereas ambition is a founder’s leverage to increase the outcome level.

If you look at the significant outcomes in VC, the companies that were later valued in the billions had founders who were more ambitious than the ones who were building undifferentiated products with an undifferentiated distribution and business model.

In the short term, how do we enable gaming startups with limited resources to increase their odds of success?

Some ten years ago, game development got obsessed with early validation. Kill your darlings.

Then, we hear that some big companies have projects that have been ongoing for years, with a beta launch that happened before the pandemic, and they are still working on the game. It feels so off in the age of killing your darlings.

We terminate game projects when we feel that the team can’t progress with the game to reach KPIs in a certain period. In startups with limited runway, it’s even more complex—eighteen months to prove the KPIs.

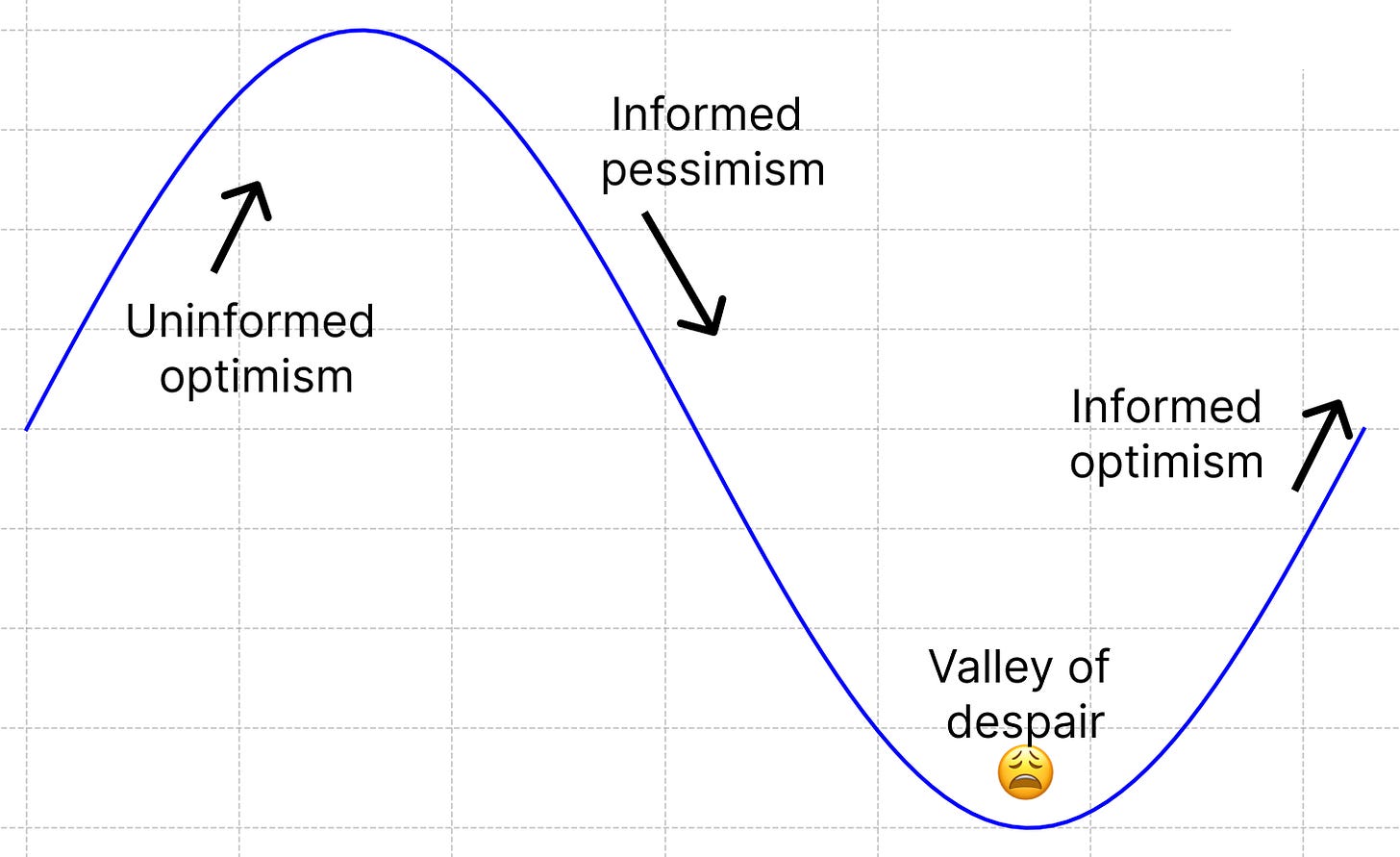

I recently started thinking about models for building a games company. The best model I’ve identified is the Emotional Cycle of Change. Introduced in 1979, the model outlines the emotional stages people typically go through when experiencing change.

The curve has several phases, starting with Uninformed Optimism, where you feel optimistic since you don’t know how hard it will become.

Then, it gets hard in the second phase, informed pessimism, where you realize the initial hurdles and start to understand that there is a steep hill that you need to climb.

After that, you enter the valley of despair.

Since game developers have been taught that you need to kill your darlings, often as fast as possible, you don’t have six months, let alone 12 months, to stick around in the valley of despair.

Many devs kill their game and start the curve all over again.

What is the solution? Gaming startups need to find ways to shorten the time in the valley of despair, and they need to persist to the fourth phase.

Game projects with lots of innovation, or copycats, will suffer. Both have long-lasting valley treks since you have too many unknowns, where the features need to mesh better, or the market needs to be more interested in your game.

Then there’s the amount of content. Games live and die, based on player retention. How will you keep making money if you need more content for players to last more than a week?

To shorten the valley, pick something that has been proven yet hasn’t been saturated on your target platform. For example, PC games have heavily inspired most successful titles on mobile. Steam is full of exciting games that might make sense as free-to-play games on mobile.

Another way is not to go back to the start of the curve but instead do a pivot whilst in the valley. The pivot might mean a significant change to the game, but you are not throwing away the learnings from the previous phases on the curve.

Whatever you do, try to avoid starting new curves. You will make it more likely that you will succeed if you persist with what you already have.

As I wrote this piece, the good people at SPEEDRUN published a podcast episode where they interviewed Mark Pincus, Zynga’s founder and longtime CEO. There are a lot of lessons there that are very applicable to gaming startups.

About the author

General Partner @ F4 Fund, Co-Founder @ Next Games (acquired by Netflix), the most helpful investor on your cap table 🫡

Please login or subscribe to continue.

No account? Register | Lost password

✖✖

Are you sure you want to cancel your subscription? You will lose your Premium access and stored playlists.

✖