It’s Time for Games to Embrace Aggregation Theory

Journal 15 Phillip Black September 9

It’s Time for Games to Embrace Aggregation Theory

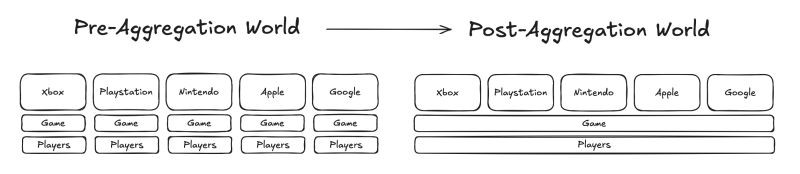

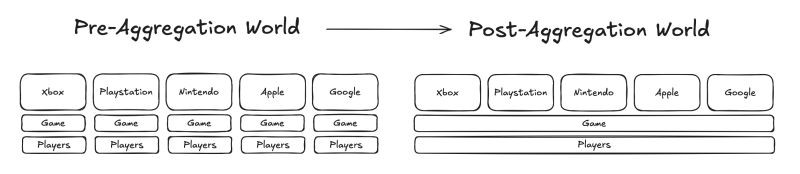

In tech writer Ben Thompson’s infamous aggregation theory, economic power derives from supply ownership—train barons owned the track and leveraged that power up and down the supply chain. The internet flipped the relationship: with near zero switching and distribution costs, suppliers instead aggregated user demand to leverage suppliers. Consider Amazon: aggregating millions of customers gained power over suppliers, compelling them to compete on its platform and play by its rules. In a post-ATT and “black hole games” world, gaming unwittingly embraced this dictionary, and distribution has become all-powerful.

Previously, games saw a lite version of aggregation theory, as platform owners like Sony and Microsoft owned the track (and thus users), allowing them to set the game’s rules. But something funny happened: cross-play, progression, and commerce crumbled console platform power as Epic leveraged Fortnite’s popularity to insert itself between platforms. Roblox grew so powerful that it bent Apple’s will, which granted it a “game-within-games” App Store exception. Roblox’s MAU nearly exceeds all game platforms combined, while Fortnite console MAU ranks first monthly. This consolidation of player bases has dramatically shifted the balance of power. The conquest continues, with Sony now allowing Discord voice chat integration on PlayStation consoles. This was unthinkable ten years ago!

Strong platforms exploit their position in and outside of games. Early MCU actors like Chris Hemsworth and Chris Evans were paid in the low six figures on the notion that their careers would take off afterward. Marvel’s power came from massive distribution, reflected in these economic relationships. The same thing almost happened at last year’s Super Bowl: artists who performed at half-time would pay the NFL instead of vice versa. While the NFL backed away, it’s another example of redrawing contracting battle lines.

Roblox has succeeded in this for the last couple of years, and Look North World’s (LNW) Gundam deal signals it starting on Fortnite. Meanwhile, the Lego and Disney deals amount to paying Epic for the privilege of player access. While Gamefam and LNW pay for licensing, Epic, and Roblox pay nothing. Instead, they benefit from the engagement uplift and revenue share from in-game items, while brands access hard-to-reach audiences and enjoy adjacent brand monetization (toys, etc). The next question is when other large games like Brawl Stars and Call of Duty will extract terms from licensors given their 150m+ MAU (nearly half the size of the U.S.).

However, growth in these mega-platforms is showing signs of deceleration. Roblox’s growth has been essentially tier three, while Fortnite’s MAU has regressed, much less grown.

Ultimately, the next phase of gaming’s evolution will test the limits of aggregation theory. Success will depend on platforms’ ability to amass players and exploit their economic power.